Lysistrata Jones is one of those peculiar shows that has a premise without which it probably wouldn’t exist, but which it would have done far better without.

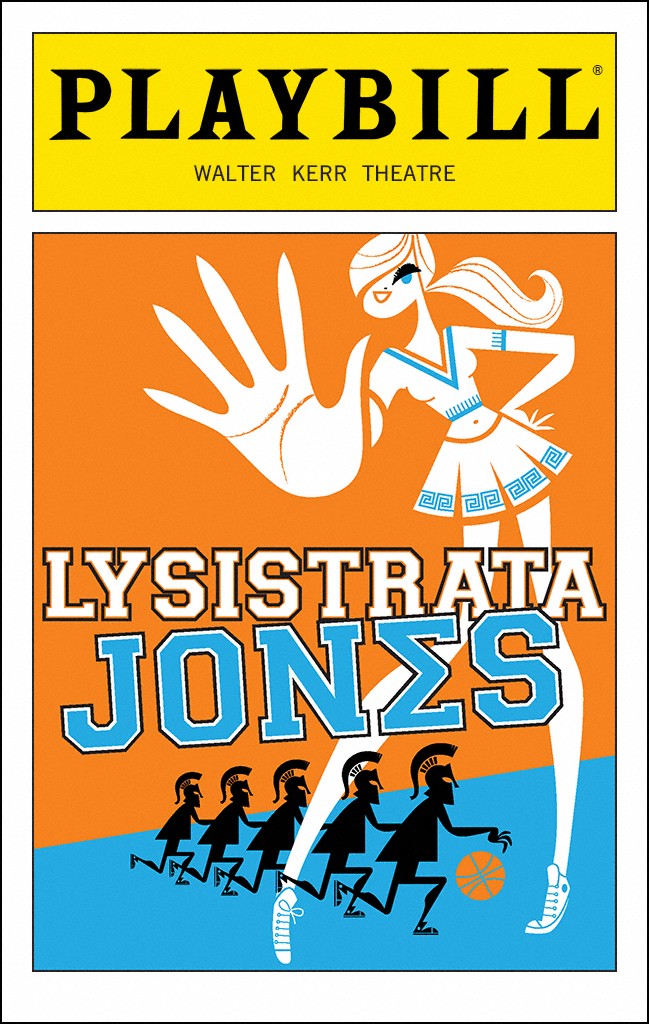

I had the good fortune to see it on Broadway in the brief window before it closed and thought it was a thorough delight. I was scarcely surprised that it closed, mind you; a show on the small scale of Lysistrata Jones tends to be easily swallowed by even a slightly too-large space, and the Walter Kerr Theatre was substantially too large.

Even though I can’t remember a single song from the show, I certainly do remember the score going down easy. This is hardly a flaw, mind you – who, other than sad nerds like us, remember any song from A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum other than “Comedy Tonight” and maybe “Lovely,” at a stretch? The songs in a farce are there to give us a brief and pleasant respite from the madcap antics, and the score of Lysistrata Jones managed that just as Forum did. And the madcap antics themselves are both funny and satisfying, with Douglas Carter Beane bringing his taste for drawing-room comedy to bear on a modern setting.

Lysistrata Jones was a show of small ambition that made good on that ambition. For what it wanted to do, it executed as well as one could reasonably hope.

There was only one problem: the premise of the show.

Lysistrata is an ancient Greek comedy by Aristophanes concerning a group of women who force their warrior husbands to stop fighting pointless wars by denying them sex until the violence stops.

The women in Lysistrata Jones, a modern adaptation of the tale, pull a similar ploy, only they are trying to get their boyfriends to stop…being bad at basketball.

…yeah…

Leaving aside the obvious antiquated stereotype of women’s value being restricted to their sexual availability, the original Lysistrata story broadly succeeds at skewering the pettiness of war; the fact that these warriors have been taking countless human lives and blithely risking their own for ages without any thought of consequence, but being denied sex is where things suddenly start getting too real is absolutely hilarious, not to mention painfully true-feeling to human (and particularly male) foibles.

Spike Lee got this. Whatever its myriad other faults, his adaptation of the story, Chi-raq, successfully conveyed the comic conceit that lies at the heart of the story by doing what West Side Story did decades before, substituting gang warfare for the internecine squabbles of a historical Mediterranean setting.

But the conceit of Lysistrata only works if what’s being held to ransom is of comically lower stakes than the thing the ransom is meant to purchase. Here the equation is sex vs. basketball, which, even if you’re really into basketball feels like, at best, a lateral move.

And I was being generous with my phrasing before – “the boys should stop being bad at basketball” is a way of framing it so as to make it seem like it hews closer to the source material’s premise, but what’s actually being demanded is that the boys get better at basketball. The point of Lysistrata is withholding sex to get the men to stop doing something stupid they probably shouldn’t have been doing in the first place. Here the denial is instead aimed at making them…get better at an unrelated and ethically neutral task.

So the premise got a setting transplant and died on the operating table. What were the practical results of this as far as the show goes?

Well, oddly, everything that doesn’t have to do with the ostensible premise is wonderful. The characters and subplots are all broad but charming, and the farcical machinations resolve with all the satisfying neatness you could hope for.

And then the show continues for a further half-hour because we have to fit in the basketball game that resolves the elements taken from Lysistrata, during which we learn the important lesson that…who knows? There is no interpretation of the show in which it would not have been immensely improved by just jettisoning the source material.

But that source material was the point, the hook on which the show was sold. I can snipe at its pointlessness, all I want, but it was never going to do the one thing that would have most helped it. Maybe, practically, it couldn’t have.

“Kill your darlings” is an old saw by this point, and frequently good advice, but I am always fascinated by situations that complicate that advice, and Lysistrata Jones is certifiably one of those. The excision of its darling might have proven fatal, but the show closed tragically early anyway, so was there any way to save it? Who knows. Maybe if they had tried denying it sex.